The drawings of August Rodin (1840-1917) have always been fascinating to me because they have a special power of observation that I associate with other great sculptors like Henry Moore, or Alberto Giacometti, or Giacamo Manzu. In fact, I often tell my life drawing students to look at the model like a sculptor, as a three dimensional presence rather than a silhouette.

There is in Rodin’s sculpture a visual precision of the human body that was psychologically penetrating and a quantum leap from the acres of pseudo-classical public art of his time. I personally consider his insight to be the result of his life-long practice of drawing from observation as can be seen in over 7000 drawings and prints in museum collections.

There is in Rodin’s sculpture a visual precision of the human body that was psychologically penetrating and a quantum leap from the acres of pseudo-classical public art of his time. I personally consider his insight to be the result of his life-long practice of drawing from observation as can be seen in over 7000 drawings and prints in museum collections.

So it was not surprising for me to learn that in his youth Rodin studied with a famous drawing teacher of the time, Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, known for his ability to first develop the personality of each student, so that they observed with their own eyes, rather than from the ideals of the past. Much later in life, Rodin still expressed appreciation of his teacher for this core skill.

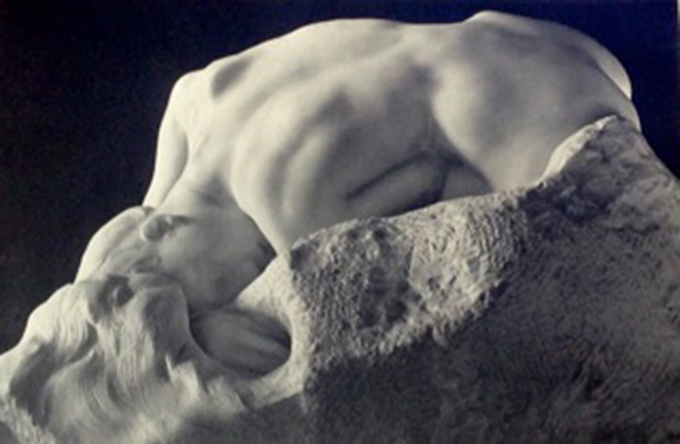

Speaking of The Thinker, Rodin said: “What makes my Thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back, and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes.”

The human body was Rodin’s medium. In his mature years, when his studio was populated with his many assistants, it also included numerous nude ‘models’ just hanging out, as it were. Instead of copying traditional academic postures, Rodin preferred his models to move naturally around his studio as his way of inspiring himself, often making spontaneous sketches on paper or in clay, sometimes later cast in plaster. The nude body focused his energies, his sexuality, and literally was his personal metaphor.

Besides the foundation of drawing in his development, his successful years were well served by his early apprenticeships working as an ordinary craftsman in the architectural sculptural shops of that time, that produced façade ornaments, porticos, entrance sculptures.

While to our modern eye architectural ornament may seem conventionally unimaginative it was technically masterful, and taught Rodin a very wide range of skills such as the sculptural techniques of clay, plaster and monumental casting. Equally important, he learned to work with others, including how to identify and hire the kind of master craftsmen that in his later years allowed him to work on many projects, some of them massive public events such as the Burghers of Calais, or the Doors of Hell.

One of his assistants was Camille Claudel who was first his student and later a friend and lover, who eventually had her own distinguished career as a sculptor. Claudel’s relationship with Rodin was life-long and tumultuous, but she often inspired Rodin’s work as critic, assistant and trusted colleague. She may well have modeled for the pose shown here.

For me, Rodin’s career is a living example of the three standards of my own teaching philosophy imbedded in The Drawing Studio’s curriculum: The importance of a steady drawing practice, the discovery of one’s own personal inspiration, and the role of learning and sharing from others along the way.

*The Metropolitan Museum in New York has an extensive collection of Rodin’s sculptures. Biographies abound, and there is a fine French movie (Camille Claudel, dir. by Bruno Nuytten, 1988) made on the relationship of Rodin and Camille Claudel and available over the internet.