Georges Seurat is considered to be the most impressionistic of the French 19th Century painters, including Monet, Pisarro, Morisot, and Renoir—-in part because Seurat was scientifically interested the new and novel ideas of atomic particle physics. In his short life he developed an almost scientific way of painting with small dots, later called ‘pointillism’. The most famous example of his style is A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grand Jatte owned by the Chicago Art Institute.

Place de la Concord, 1883

Historians have speculated endlessly about the strange anomaly between the cheerful color of Seurat’s impressionist paintings and his brooding dark drawings. While his paintings were quite colorful, most of his drawings were simple compositions from life, and often included the poverty and the winter barrenness of the new industrial zones of Paris that do not appear in his paintings.

Why the paradox? One of the things I have discovered is that art scholars who have never worked in a studio sometimes build complex cerebral theories about what can be an obvious and often practical explanation to a working artist. So here I presume to offer what I see in Seurat’s drawings from life.

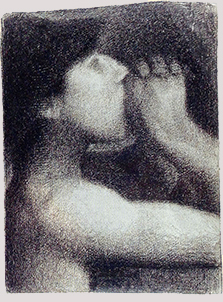

The Echo (study for Baignade) 1883

The examples shown with this essay were drawings done between 1881 and 1888. They are all the same size, and made on sheets of very rough hand-made paper called Michallet, which means that Seurat most likely drew in a sketchbook. A sketchbook (or portable portfolio of standard sized papers) was a new concept in his time because artists did not just work in the studio anymore.

As hard as it may be for plein-aire painters of our time to understand, the idea of working from the ordinary world around us was a new and underlying insight of the French impressionst movement. To hold the ordinary world as sacred and relevant art was revolutionary and counter to the existing classical ‘conceptual’ painting based upon the often shop-worn tableaus drawn from mythology, religion or politics.

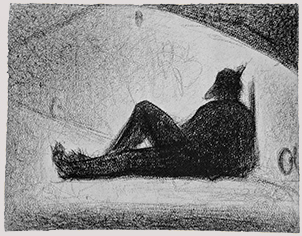

The Tramp, 1883

In other words Seurat’s sketchbook itself was a new crucible of visual thought. With his portable studio he could range the physical world for fresh insight, taking his studio TO his subjects, his family settings etc, then using the drawings and (as important) the experience of what he saw around him, to inspire the production of larger paintings done for sale.

Embroidery (The Artist’s Mother), 1882-3

In practice however, Seurat’s work remained studio-based. He certainly could not ‘paint’ outside, given his labor-intensive pointillist style. So I think he happened (accidentally?) upon a simple and portable medium of rough paper on which he used a waxy drawing stick called conte crayon, to produce a look-alike pointillist drawing—not by drawing point after point, but by skimming the surface of the rough paper so that in a brief sketch he can create the illusion of his pointillist painting style. By scrumbling broadly over the high ridges of a rough drawing paper made for watercolor, he had found a metaphor that simulated his impressionist manner of the dots of color in his paintings.

At the same time, what I notice about these small drawings on rough paper is how incredibly original and inventive they are both as compositions and in the way they capture light, mood, and drama in a kind of chiaroscuro short-hand. Clearly these works from street life testify to the source of Seurat’s work as rooted in drawings done from the practice of very direct observation of the world around him.

My students at The Drawing Studio are probably weary of my pointing repeatedly to the role that drawing from observation plays in the work of our greatest artists like Georges Seurat–but it’s true.

4 Responses to Georges Seurat (1859-1891)