As I was writing my recent essay on the paintings of Joan Mitchell, I realized that the number of women in the United States besides Georgia O’Keeffe that I knew about for their contribution to contemporary art before 1945 had been to say the least, very modest. The biographies included in the National Museum of Women in the Arts reminded me of others, like Alice Neel, Isabel Bishop, Helen Frankenthaler etc, but they were mostly artists who only became visible in the post-War years, long after O’Keeffe’s earliest exhibition in 1918.

That is not to imply that the practice of art was not a serious pursuit of women in times past. In the 19th century in Paris a few women who worked as professionals begin to appear, like Berthe Morisot, Suzanne Valadon, and the American Mary Cassatt. But until then we have to note that few women had the opportunity to insert themselves easily into public life anywhere. And further, the few who did have some access were so limited by the gendered response to their work, often used by critics and historians to ‘disqualify’ their art from the mainstream.

Figure 1: Alfred Stieglitz, portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe

It is equally obvious, however that until the twentieth century, the role of art in family life was almost solely passed along by women, even to their men children whose fathers seldom if ever supported an art career. For example Maurice Utrillo was the son of Suzanne Valadon. It was also clear that the mother of John Singer Sargent was an avid amateur and without question his first and most serious coach and mentor. I would also recommend the splendid two volume biography of Henri Matisse by Hilary Spurling, which traces the seminal influences of his mother and many of the women who supported his career, some of them becoming practicing colleagues themselves.

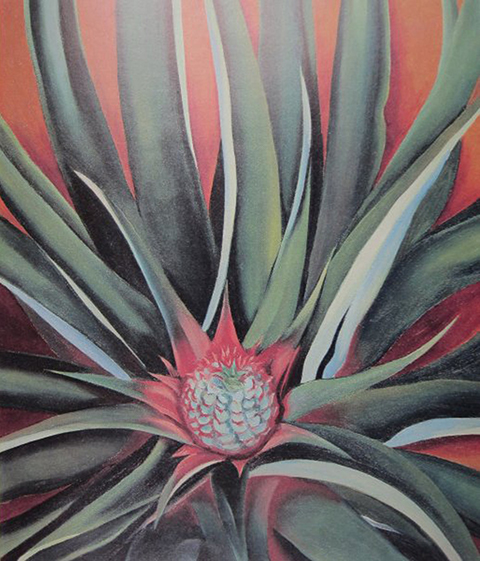

Figure 2: Pineapple Bud

O’Keeffe’s early path of study included the Art Institute of Chicago, The Art Students League, and teaching positions in Virginia and Texas. However it was her remarkable drawings that first brought her to the attention of Alfred Steiglitz, who was not only an original modern photographer (see his study of O’Keeffe, Fig. 1), but whose small gallery in NYC was an early and unique showcase for modern art.

In 1925 O’Keeffe’s work was shown for the second time by Steiglitz, who by then was her advocate and lover. Her large paintings attracted a lengthy review by Edmund Wilson. A few excerpts below reveal how quickly she was recognized as a major painter, comparable to John Marin and Arthur Dove:

Her new paintings in the Stieglitz exhibition at the Anderson Galleries are astonishing even to those who were astonished by her first exhibition two years ago …. For one thing, she has gone in for larger canvases …. Yet at the same time that she has allowed her art to expand in this decorative gorgeousness, she has lost nothing in intensity—that peculiarly feminine intensity which has galvanized all her work and which seems to manifest itself, as a rule, in such a different way from the masculine.

Figure 3

Whether or not we can assign her interest in the seminal world of plants and flowers to her femininity (Pineapple Bud, Figure 2), we can observe that her early interest in botanical themes went through many stages, growing new tendrils as it were, that continued to express ever deeper metaphors of life-force as the years passed, far beyond any simple-minded discussion of female anatomy. (Figure 3).

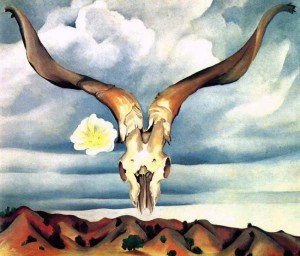

Figure 4: Ram’s Head

During the thirties, her life and interests abandoned the male dominant intellectual art center of New York upon visiting the Southwest, where she found for the first time the spiritual homeland she was looking for. In New Mexico Georgia O’Keeffe discovered her heartland, her freedom and her passion for the undomesticated wildness of the desert that inspired her art for the rest of her life. (Figure 4)

Figure 5: Juniper Flower

Like her American male contemporaries (Marin, Dove) O’Keeffe’s vision quietly broadened and realigned the modern influences from Europe that flowed from the 1913 Armory Show by applying its lessons to the American landscape as a modern movement in its own right. In 2014, 28 years after O’Keeffe’s death at 98, her stature in the American history of art brought the highest price ever paid at auction for an American woman painter, 44 million dollars for her Juniper Flower oil (Figure 5).

One Response to Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986)