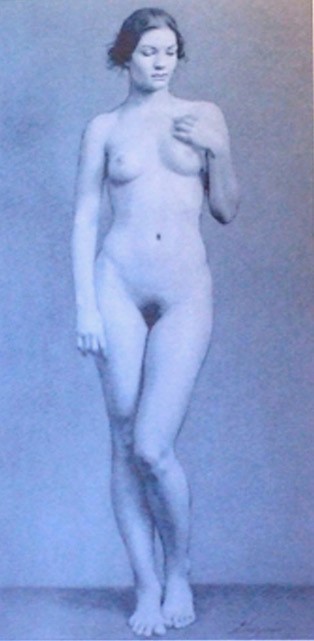

Drawing from the nude human figure has been taught for centuries in mostly in the same way, i.e., based a classical Greek philosophy in search of abstract ideals of perfection.

(Figure 1)

(Figure 1)

This bent toward the ideal shows up in the modern figure drawing class as the ‘space’ around the figure that is often ignored, as if the figure were a spaceship floating on the paper in some kind of ‘ether of no-where’. This tells me that while the drawer is technically absorbed in being accurate, they are not necessarily aware of or engaged in the presence of the figure as a person, living in the world we both share, mentally and physically.

When one is drawing a landscape, it is obvious from the first stroke that ‘space’ is involved. What is near or far, what is in or out of focus, the mood and light of the day must be translated into physical shapes and values on paper in a way that evokes the richness of the spatial experience before one’s eyes.

The opportunity that drawing from the figure presents us is absolutely unique because it is actually a meditation upon being human in the world we all live in. For instance, one cannot draw a person without being aware of our shared physicality on both a visible and a spiritual level.

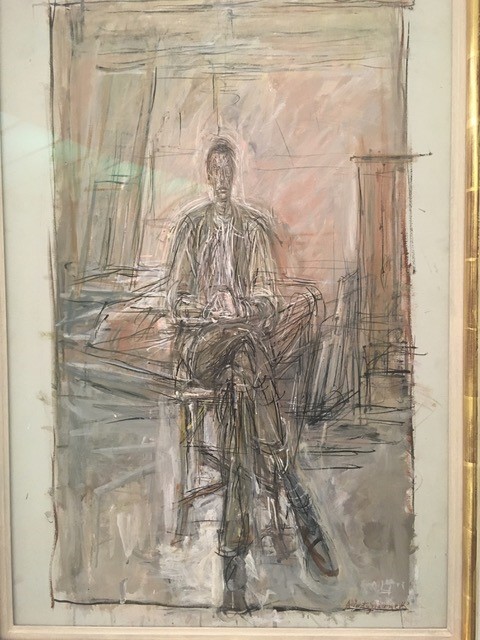

(Giacometti)

(Giacometti)

In the same way, the body cannot be understood apart from the space in which it lives any more than the leaves on a tree can be drawn without dealing with the space around the leaves.

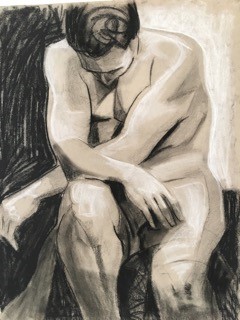

(Paul Mohr)

(Paul Mohr)

After years of teaching drawing, I can tell from a single figure drawing whether the artist sees the model as a thing, separate from the environment, or as part of the whole, interacting with gravity and aging, with cold and heat, and even reflecting elements like fear, love, sadness, all of which I think of as the human ‘landscape’.

A successful figure drawing can and should reflect the space in which the body exists (Chilton). Some aspects can be shown visibly, like the shadow next to the body (Steinberg) others are subtler, like the sadness that shapes the mouth, or the weariness in the eyes (Picasso). A memorable figure drawing implies the ground on which the model is standing, the air they are breathing, the quality of the day’s heat or cold, the heaviness of gravity pushing upon the hip, and yes, even the beauty of a negative shape that vibrates next to the skin tone of the thigh.

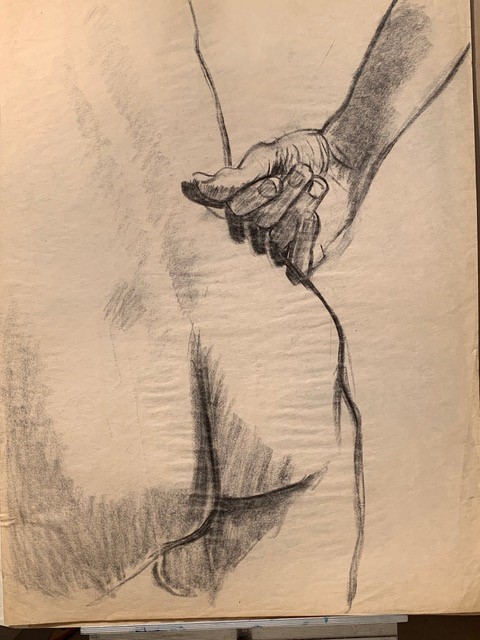

(Nancy Chilton)

(Nancy Chilton)

(Deb Steinberg)

(Deb Steinberg)

(Picasso)

(Picasso)

Limiting one’s focus to technical skills can also be traced to the hidden presence of our early American cultural context as shaped by Puritan Christianity—i.e. bodies often involve either desire or shame, affecting how we look, or don’t really look. Therefore, in order to address the deeper possibilities of drawing the figure, the beginner must first look to their own attitude and past mind-set.

This is easy to do in our Drawing Studio drawing classes where we cultivate the skills of ‘just looking’, in the presence of the warm immediacy of an experienced human model and surrounded by our fellow students. Here we have the full permission to ‘look’, to discover a much richer experience far beyond desire or shame, one that approaches a spiritual insight into human existence itself, including our own.

Here are some of the ways I have found useful to draw the figure in space:

a. For an extended pose, I spend a few minutes bringing my attention into focus, just quietly looking, gathering the ‘feeling’ of the pose. Sometimes I walk around the model, to take in the 3-D nature of the pose.

b. I also become aware how the body is interacting with gravity. Sitting, standing, lying down, leaning against some prop or wall, the body uses all kinds of engineering strategies to spread gravity to hold itself up.

(Paul Mohr)

(Paul Mohr)

c. I also like to consider the ‘mood’ of the model in that pose—heavy, light, quiet, active, etc.

(Andy Rush)

(Andy Rush)

d. Then I include a moment of reflecting upon my own mood – calm, restless, interested.

e. Finally, I make a choice about what I am going to draw, i.e., how I want to work, how to best reflect the energy of this model or this pose. One might select a detail versus the whole body or choose to simplify the big forms, or relying on light and shade for dramatic effect, or using linear energy, or heavy dark units to emphasize weight and mass.

(Andy Rush)

(Andy Rush)

(Andy Rush)

(Andy Rush)

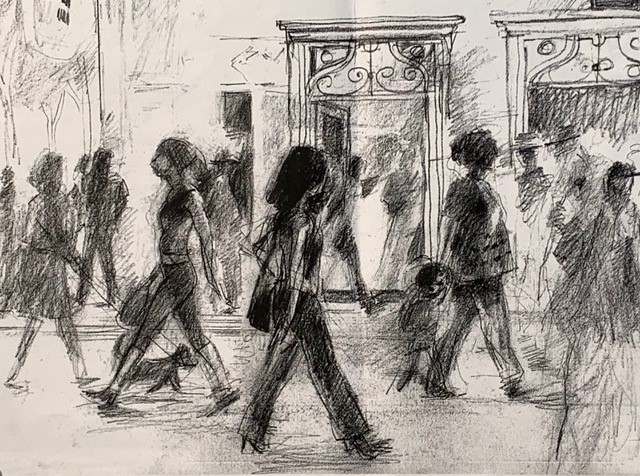

f. Then in my personal life after class, I continue to ‘draw’ mentally by watching people around me throughout my day. Waiting in line or sitting in a group (like airports) are precious opportunities to look at people, at various bodies and ages and how people manage their bodies to get through the day. Your next figure drawing session will seem much richer as you practice mental drawing throughout your ordinary day.

(Andy Rush)

(Andy Rush)

In the final analysis I would say that figure drawing is one of the most effective practices for developing more connectivity and empathy with being human in all its forms, and at times, even addressing the personal existential loneliness we all sometimes experience.