My first awareness of the French artist Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) was when I was a student in the fifties. I first saw only his elegant graphic art, which was how he made his living in his early years, just like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, his contemporary. It was not until much later that I had opportunity to see Bonnard’s original paintings.

Where had they been, I wondered? In my student travels I had seen almost none of his paintings in public collections, but later learned that during his lifetime most had been sold to private owners, where they stayed out of public sight for years. That generation of private collections have only recently began to break up to become re-available, so when I saw two public exhibitions of his original work in New York around 2000, I began to understand why their first owners were so fond of them that they rarely appeared in public.

I think the first reason is that while his paintings were intimate and complex, Bonnard’s compositions mirrored the world of middle class urban people like himself, which made his work familiar and accessible to a new ‘middle class’ of collectors produced by the wealth of the industrial revolution sweeping Europe in the late 19th century.

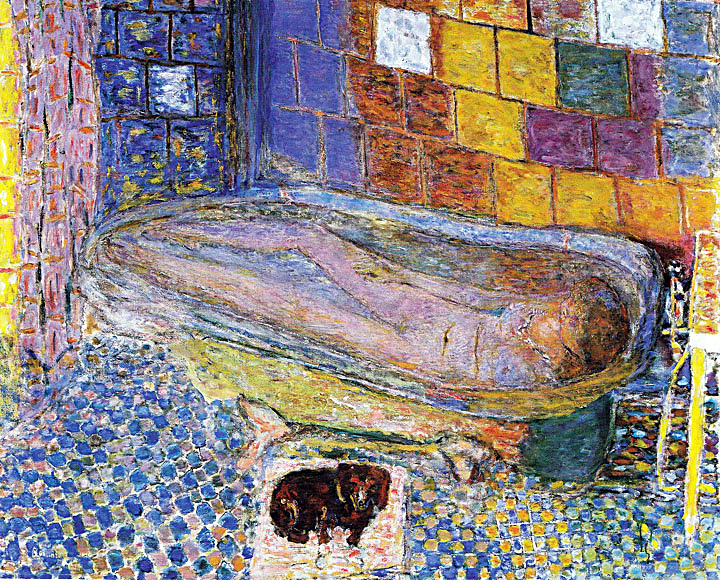

Second, he had an eye for pattern that rivaled Matisse, who generously declared Bonnard to be one of the greatest artists of the time. Bonnard endlessly invented new points of view with his compositional skill, still conventional but often from unexpected perspectives, so that he let people see the familiar in a fresh way.

Third, his use of color was original, often wild and intense, and applied layer upon layer to produce a depth of richness that can renew a painting over repeated viewings. Such color richness, so seductively interesting in the original, just cannot be fully captured in reproduction.

And finally Bonnard possessed a sophisticated visual wit, sometimes hidden in the detail and sometimes hidden in plain sight (note the little dog on the rug). Such layers of meaning and layers of form gives each of his paintings a singular, personal and almost an iconic presence any owner would find hard to give up.

The example I have I selected to accompany this essay demonstrates in my view all these qualities mentioned. It is titled Nude in the Bath and Small Dog (48” x 59 1/2”) and was done in stages between 1841 and 1846. The woman in the bath is almost certainly Bonnard’s wife, Marthe de Meligny, who suffered in her later life from many maladies probably including shingles, which may account for both the hours she spent soaking in the bathtub, as well as the number of paintings Bonnard did that are similar.

What is interesting to know is that Bonnard did not paint from life, but from many preparatory drawings, color notes, small compositional sketches and sometimes photographs he took. For him, each painting thus became a kind of production not unlike a movie, a reality of it own, a dream meditation that could occupy him for years as this one did.

To learn more about Bonnard there are ample references on-line, but for a concise summation, see the Tate Catalogue, Bonnard by Sarah Whitfield, 1999, which includes a comprehensive Select Bibliography covering his paintings, drawings, and prints.