Regular readers of Andy’s Window may have noted that my essays have recently focused upon some of my Tucson artist-friends. At my age of 84, I realize that our flow of work and ideas has been constantly interweaving with each other over sometimes for decades. As I write here about the portraits we have made of each other reveals to me for the first time a kind of tapestry of wisdom that has a richness beyond any one person. So I may stay here for few essays, continuing to write about the artist friends who inspire me, and in hopes that you too start to look and acknowledge those artists closer to your life who inspire you.

My recent essay about the human torso as an art theme used by artists cross-culturally throughout history has led me to look for other such shared subjects. Landscape may be one. Botany another. But portraiture certainly ranks high on the list.

The human face appears everywhere across the spectrum of art history. Recognizable portraits (often highly stylized) have been used since the Roman Empire to give authority to power (statuary, posters, coinage, e.g.) or to religion and mythology (gods, goddesses, holy personages etc). However with a few exceptions—like the Coptic grave portraits of the first century AD—modern portraiture is the child of the secular humanism that is almost the core religion of our time. That is to say, portraiture of ordinary people is relatively speaking a modern phenomena.

Before photography, it was the great artists of the European Renaissance that gave us the first images of the individual person, starting with selective portraits of the powerful (Velasquez, Holbein, Goya, Franz Hals), followed by images of the new commercially wealthy (Rembrandt, Rubens, Ingres). In time there appeared the images of artists’ friends and family, then street beggars and peasants, and eventually even oneself.

From Rembrandt (Figure 1) I personally adopted his habit of making a self-portrait frequently throughout his life. I do it at least once a year (Figure 2) because I have found something helpful about staying visually current with myself, including processing and accepting the shock of aging since last time. In the same way, my portraiture of family and friends is a record of the intimacy of our years together in many ways more telling than photographs. (Figures 3 & 4)

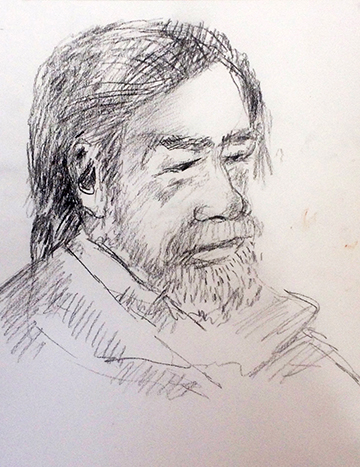

Charles Littler, the founder of the Rancho Linda Vista Community, created ‘family’ portraits that were inspirational to many of us. (Figure 5) His self-portraits especially (Figure 6) were highly exploratory. He also made many large charcoal studies that often took him years of sittings that reflected the many chapters of his life-long friendships. (Figure 7)

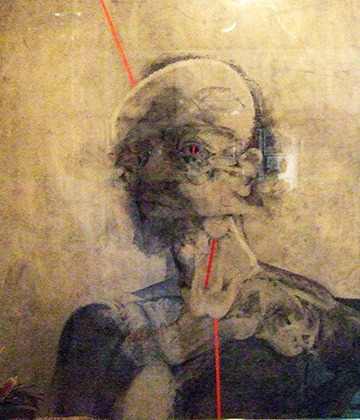

One of those friends, Steve Romaniello, was the subject of a the large charcoal portrait (30 x 40) Charles made of him (a study spanning several years of ‘afternoons with Charles’. (Figure 8) Inspired as we all were by Littler’s way of working, Steve has recently launched a long term project of large (4–5 ft) facial portraits of some of his closest friends. Each painting involves a process that takes the likeness far beyond a simple cosmetic presentation into a realm of almost ageless presence. (Figure 9)

As the sitter for one of them, I watched my (aging) face as it slowly appeared on the five-foot canvas, like a huge landscape of the acres of my wrinkles and pimples like mountains and valleys. At the same time I could see that Steve’s painting contained a kind of ‘suchness’ that was really me in ordinary life, like in the morning just out of bed and before its time to prepare myself for the outside world. As Steve said at one point, “I notice that the more years I have known my friend in life, the more the painting captures a true essential likeness”.

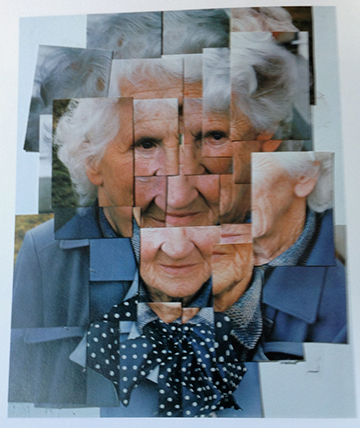

Steve’s project is also just one dimension of the profound possibilities of the realm of portraiture of friends. David Hockney, the British/American artist used the Polaroid camera some years ago to explore how we actually see in small units, rather than the traditional snapshot. His portrait of his mother (Figure 10) is an example of this absolutely new contribution to art, that still resonates in its implications for new vision a quarter of a century later.

And I could not conclude this essay without recommending the book Man with the Blue Scarf by Martin Gayford, which is his insightful account of sitting for his portrait over several months with his good friend, the British painter Lucien Freud (Figure 11), one of the greatest portrait artists of our time. At the end of his book, Gaylord says “… (the portrait) is me looking at him looking at me. There are many elements caught in this image: time, passing moods, feelings. It’s a record of all those hours of conversation, and of just silently being together in this room.”

We at the drawing studio continually offer portrait classes. Upcoming are Deb Steinberg’s three session Introduction to Portrait Drawing, April 5 -19 (1–4 PM) and Judy Nakari’s Portraits in Watercolor, May 1-22 (1-4PM).