“I am a writer who draws.” –Saul Steinberg

“(Saul Steinberg) was the wisest person I ever met in my entire life.” –Kurt Vonnegut

My life-long fascination with how images and words are related has led me over the years to look deeply into the lives of those artists whose vision has opened new doors for me. And I have discovered, beyond who their teachers were or where they went to school, that the most valid clues that point to the foundation of their art are found in the smallest traits of family and personal character, along with the randomly fated details of their individual life.

As a personal example, my art is rooted in one certainty, which is that words and images are joined at the hip. I never thought about where that idea came from until I recently remembered my long forgotten father Harvey, who was a writer in his very short life, confined in his last years to a tubercular sanatorium. He must have known about words and images too, because after spotting my young drawing skills and without missing a beat he took me to meet Lee Falk, the artist who drew Mandrake the Magician, a comic strip of the time, in his working studio. In retrospect one must remember that in my youth (1930s) there were no artists in sight, no art supplies, no childrens’ art classes, not even in high school. It was that one gift of my father’s simple recognition of who I was that set the compass of my life from that point forward.

A second example: Beatrix Potter (1866-1943), who drew and wrote the first children’s stories around the character Peter Rabbit was only home-schooled like all well-bred English girls of her time. Left mostly to herself during childhood summers spent in the country, she became a keen observer and collector of small animals, out of which she developed a scientist’s sensibility, as well as eventually writing and drawing the stories that shaped a new domain called children’s books for years to come.

If Saul Steinberg had been born in America (instead of Romania in 1919), it is doubtful he would have ever become the unique kind of ‘word-image’ artist he was. Steinberg was first of all shaped by being a Jewish student in Italy, when Hitler and Mussolini were rising to power. He first studied philosophy and later architecture in Milan, so he was early on steeped in renaissance and humanistic culture. His entry into ‘art’ was in a sense by the back door, as his visual wit found him making cartoons for the satirical Italian magazine Bertoldo, where he found the medium that was waiting for him.

Figure 1

In 1940 Mussolini passed the first anti-semitic laws in Italy, which drove Steinberg first to the Dominican Republic and then, thanks to the sponsorship of The New Yorker magazine, was admitted into the U.S., in no small part due to the originality of his edgy cartoons, first published by The New Yorker in 1941.

Steinberg quickly paid his dues as a new American, by serving from 1942 in military intelligence, where his multi-lingual and political European savvy was clearly an asset to the war effort.

After the war, Steinberg’s visual wit eventually became the visual philosophy of The New Yorker. The brilliance of his magazine art and cover pieces set the standard for a new edgy cultural commentary that became a welcome and very witty ballast to the flatulent over-wealthy pretensions of the media of modern post-war New York.

Figure 2

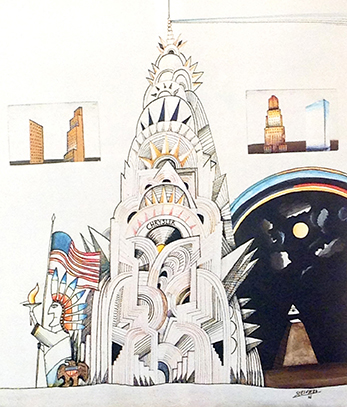

Less well known was that his public work was a distillation of a vast private studio practice, where Steinberg endlessly explored and experimented with how images communicate. His works were often collage-like constructions (think Kurt Schwitters) extracted from the detritus of mountains of commercial printing (think pre-Rauschenberg), recontexturalized mass-products, like paper bag portraits (think pre- Warhol) along with all kinds of biting visual take-downs of the authority of stamps, passports and diplomas and other sealed and signatured documentary pretense (Figure 1).

Figure 3

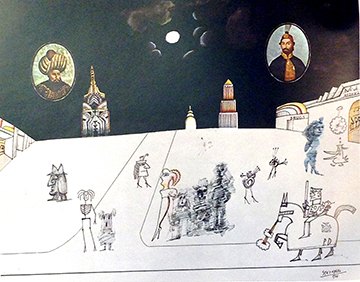

His background in architecture was never far away. His cartoons often used buildings as satirical personalities (Figure 2), that mimicked the pretenses of urban power and its irrelevance to the suffering of its human values (Figure 3).

Figure 4

His portraiture however can be easily missed, because he used both changes of drawing style and historic-bound imagery to depict personality in the same picture, metaphors for the way humans dress up as avatars as well as conceal their vulnerability, all projecting the underlying existential loneliness of the new large industrial city (Figure 4).

Figure 5

While it could be said that The New Yorker was his museum (both personally and in his influence on generations of new cartoonists), let us not forget that his absolute uniqueness was quickly and well understood by his contemporaries. Steinberg was one of the major American artists of his time in the 1946 exhibition at MOMA in New York, entitled “Fourteen Artists” which included Motherwell, Gorky, and Noguchi (to name only a few).

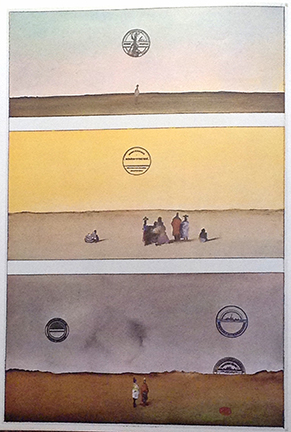

For me personally, however, I am ultimately seduced by the elegance of his simplest visual creations, made with a few marks or colors, like these “postcards” (Figure 5). Steinberg can somehow make me look anew at what’s on my own desk as an art opportunity, namely at the everyday media in front of my nose, called my correspondence.

One Response to Saul Steinberg (1914-1995)