Ingres’ manner of drawing was as new as the century. It was immediately recognized as expert and admirable. If his paintings were sternly criticized as “Gothic,” no comparable criticism was leveled at his drawings. —Agnes Mongan

Portrait of Mme. Baltrad, 1836

The role of portraiture in art–meaning the attempt to represent the specific likeness of a secular person (rather than an ‘ideal’ or generalized icon) shows up only rarely in the history of art before the coming of the humanistic age of the individual in Europe.

Two earlier secular portrait traditions include the Coptic encaustic tomb portraits in north Africa, ca. 100 AD. These were commissioned when the sitter was in their thirties, to assure their best image accompanied them into the afterlife. At the same time the Roman portrait sculptures of ca. 100 AD revealed a very secular culture in which the specific royal ruler and family were depicted with sometimes brutal accuracy.

Around 1400 in Italy, we begin to see, in the corner or background of many large commissioned religious paintings, an accurate study of the donor, and occasionally the artist himself. And by 1600 in Europe a merchant class of wealth began to emerge that gave rise to portraiture as a business, small paintings that recorded the new secular patrons, their wives and families, often decked out in their finery of clothes and jewels to communicate wealth or importance. From that point forward portraiture was central to many painter’s livelihoods, at least until the invention of photography in the mid 19th century.

Like many famous French artists of the 18/19th Century, Jean François Dominique Ingres was trained in the official academic manner, to paint the portraits of royalty, as well as to invent large salon-style paintings of historical or mythological subjects. But with the political revolutions in Europe, such traditional sources of patronage basically dried up. At the time of the French Revolution Ingres was isolated in Italy (1815-25) where he regularly submitted salon paintings to Paris, but into the face of scathing criticism (more about that later).

However he got by financially by doing very elegant and precise small pencil drawings for tourists, mostly English—at very good prices because of his well-deserved reputation as a French Academician. We now know of over 500 such pencil studies, which now are considered the most accomplished part of his work.

Some years ago I read with great pleasure an informative book by David Hockney, entitled Secret Knowledge, in which Hockney makes a most convincing case for the early role of the lens as an artist’s aid ( well before the invention of mathematical perspective) demonstrating the use of the Camera Obscura by Vermeer and later, the Camera Lucida by Ingres. The Camera Lucida is a small 45 degree prism mounted on a thin wire stand through which the image of the model is deflected face down onto a piece of paper laying flat before the artist, who can then trace over that reflected image on the paper. The size of the drawing is standard (9” to 15”). Hockney points out that most of these were pencil studies (graphite was a new medium a that time, by the way) and were drawn always on a hard wove paper of a standard 17” size, which allowed Ingres to easily erase/modify his first notations.

I have no doubt Ingres that was attracted to this device in making his pencil sketches of clients who were passing tourists, because since he had no possibility of getting to know them over weeks of sittings (as he would have done for a classic portrait from the higher classes), he could quickly establish a likeness in an hour or less, and then embellish it at leisure.

I have myself used the Camera Lucida, and so I know that an artist cannot continually use the aid for very long, since both artist and model both have to hold your head/eye very still while making the tracing of the projection on the paper, which also can be quite dim.

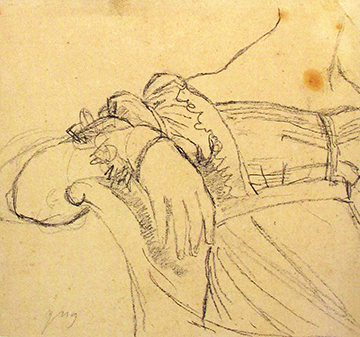

Figure 1: detail of hands

Figure 2: drawing of woman, showing hands

This precise casting of the first image onto paper with the Camera Lucida gave Ingres’s first pencil sketch a level of verisimilitude far beyond the generalities of casual observation. Hockney makes it clear with simple examples of Ingres drawings by eye and through the Camera Lucida. (Figure 1 by eye, and Figure 2 with the camera lucida) We also have a solid report from his assistants that he spent no more than four hours on each drawing, 1 1/2 hours in the morning and then a finish session in the afternoon.

In the repeated use of the Camera Lucida as a starting point, Ingres no doubt was literally drilled in a new distinction of seeing the optical whole as a unit as a place to begin. Thus the Camera Lucida gradually informed Ingres with a new understanding of how to capture the presence of each unique sitter, rather than impose a kind of ‘classical’ idealistic generality that was deep in the training of salon painters. Little wonder that his portraits and salon paintings seemed raw to the juries of the time who were still looking for an idealized beauty.

Figure 3: M. Bertin drawing

Figure 4: M. Bertin, oil painting

However in Italy, his pencil drawings were most attractive to the tourist sitters who paid him, because not only did they receive the energetic work of a great artist, but also a likeness that matched their own perception. Indeed in those sketches can be seen a harbinger of the photographic likeness just around the corner.

Many years later at the height of his powers, Ingres painted the extraordinary portrait of M. Bertin (Figures 3 & 4: shown here with a preliminary drawing) in which one can now see that Ingres’s precise observation as learned from the Camera Lucida is now a part of his natural observation, and the powerful core of his contribution to the modern movement to come.

One Response to The Pencil Portraits of Jean François Dominique Ingres (1789-1867)