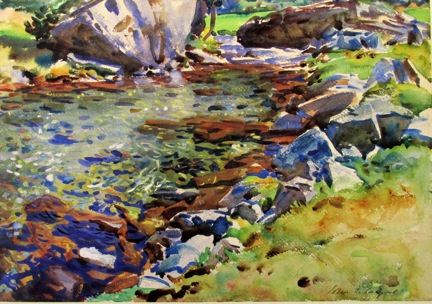

“To live with Sargent’s water-colours is to live with sunshine captured and held, with the luster of a bright and legible world” –Evan Charteris (1927)

I must confess up front that I am ambivalent about the work of the artist John Singer Sargent. While I have never had more than a mild interest in his portraits and salon-sized paintings, I have always been completely enthralled his watercolors.

Sargent was an American, but lived in Europe almost all of his life. Born to a well-educated family, most of his young schooling consisted of travelling in leisure with his parents throughout modern Europe, visiting museums and spas and following the seasons of the year. Without doubt his great visual intelligence evolved from his early and direct exposure to the collections of original Renaissance art of Europe which he studied, drew and copied along the way, strongly encouraged by his mother.

The downside of such a private and insular education was that even though Sargent was a contemporary of Van Gogh, Whistler & Homer (and only 15 years younger than Cezanne), he was more the precocious child of western art history than a direct product of the modern movement. This seamless lineage with the post-Renaissance traditions of Europe did however give him access to the ‘art establishment’ as much of his art does even now, with its many wealthy but often conservative patrons who are still truly dazzled by his compositional invention, flattering portraiture and brilliant brushwork (ala Velasquez).

At the same time, and even after decades of fame and commercial success, he was often dismissed by modern American critics like Roger Fry, Mumford, etc., as a brilliant but empty talent, ultimately irrelevant to the future of modern art. Part of his ‘problem’ (as I see it) was that while his formidable technical performance as displayed in his commercial portraiture and salon paintings made him hard to ignore, what was missing was something either personal or ‘new’ that did not already exist stylistically.

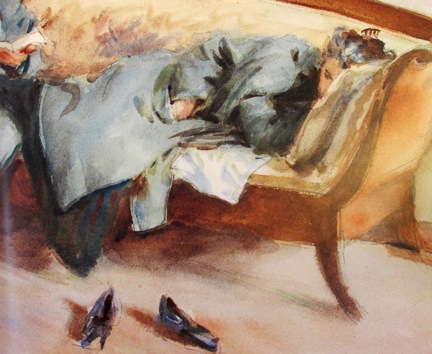

Sargent could of course feel the heat of the new energy of the modern movement, and deeply longed to be part of it. Even he recognized the paradox of his public success, but underneath he was always an optimist and more importantly, a great private learner. Thus it was in his watercolors that there emerged an authentic observer of the real world around us (vs the ‘pictorial’ world of the salon). Indeed, the directness and energy of his watercolors have by now inspired many generations of artists, including myself, to the practice of painting from life outside the studio.

In passing, we can note that there had been for decades a minor watercolor interest as an extension of sketch/drawing. It was often part of the cultural education of upper-class women, dilettantes and even travelling scientists like Darwin. But in the early nineteenth century came the first modern colors, born of the new chemical processes, along with the lead tube which allowed for portability and fresh paint at hand. From that point forward, the medium of watercolor became attractive to serious artists like Sargent, Van Gogh, Homer, and Cezanne, because it allowed one to work directly from nature and away from the formality of the studio.

Later in life, Sargent confined himself to watercolors when he no longer was as interested in the commercial production of portraiture, producing the first body of watercolor work equaled only by Winslow Homer. And as DeCharteris noted (above), his best pieces were pure magic of the moment, ‘sunshine captured and held’.

It was only at the end of his life that this essential Sargent was finally acknowledged when the Brooklyn Museum bought 83 of his watercolors at once.

3 Responses to The Watercolors of John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)