About Jim Waid, Tucson Painter

One of the ironies that most living artists recognize is that, with few exceptions, one’s own home town is seldom aware of the quality and talent of many of its own. For instance, the great 20th century Italian painter Giorgio Morandi lived all his life in Bologna, and were it not for the attention of one prominent art historian it is likely he would have been unnoticed by all but a few other painters.

Tucson has for years been the home of many of this country’s most creative people in many fields, some combination of its climate, its rich multicultural history, its majestic and available desert. Its residents have included musicians like Linda Ronstadt, medical innovators like Andrew Weil, poets like William Pitt Root, as well as artists like Curt Brill, Pat Dolan, James Davis, Charles Littler, Bruce McGrew, or Gail Marcus Orlen. I add Jim Waid, a Tucson resident for over fifty years, whom I consider as relevant and memorable to this century’s art as any painter I know.

By way of introducing you to Jim Waid’s work, I offer a few examples of Waid’s large paintings, in hopes that my remarks may encourage you to take a deeper interest in Jim’s way of seeing (see footnote below*).

While it is obvious, I want to underscore that Jim is a painter. However, that simple distinction is often lost in the abundance of uses to which the act of painting can be put, for example, illustration, design, narrative, and advertising.

Jim Waid made the choice to develop as an individual painter, in the 900-year-old historic tradition of western painting as a major medium of personal, visual and spiritual discovery. While the nature of such painting is individual and intensely private, Waid is always equally aware, part of, and inspired by his heritage and family of fellow painters both living and dead.

Before commenting on individual painting, I offer a few generalities about his work:

a) As my art students know, I use the word ‘abstract’ rarely and with care. In my experience once one takes a deeper interest in any artist’s distillation process, the roots of most artist’s images are quite ordinary, personally intimate and often obvious. In this sense, while Jim’s painting may be called ‘abstract’, it is clear to me that the primary source of his inspiration is the natural world, and to a large extent our own Sonoran Desert.

b) However, while Jim’s paintings are clearly derived from his years of organic interaction with the desert, they are neither illustrative nor decorative. Rather, each work is a personal adventure that becomes an individual symphony of shape, form and color, with layers of mood and feeling that allows us to expand our own visual world with him.

c) The paintings shown here are big (6 to 8 feet), meaning they are meant to occupy one’s attention as a phenomenon that must be engaged completely. Each is its own universe, arriving at its own conclusion generated from its own life force as revealed in the making, and probably as much of a surprise to Jim Waid as to the rest of us.

Now some personal reflections upon individual paintings:

(Fig. 1) Niobe: 1999 60”x72”: The only ‘geometry’ here is the rectangle of the painting. While the smaller units are organically derived from the desert, they are crisply re-designed and laid out in columns, to become decorative elements against the red field, thus inviting us to see in two domains at once.

(Fig. 2) Burnt Wells: 2013 60”x72”: This painting is kind of map that reminds me of my own walks in our desert, so full of layers of life, traceries of bugs, snakes and small birds and mammals, plants, cacti –all busily interactive, nothing ever still, as life goes on with or without me. I would never tire of the adventure of looking and re-looking.

(Fig.3) Diur: 2016 60”x72”: All the desert elements here, including the big tree, are painted with the smallest of brush-touches, replicating life-energy as the constant interchange that flows among all life forms. Simultaneously, the tree is an organizing presence, a kind of hotel, providing home and shade and safety.

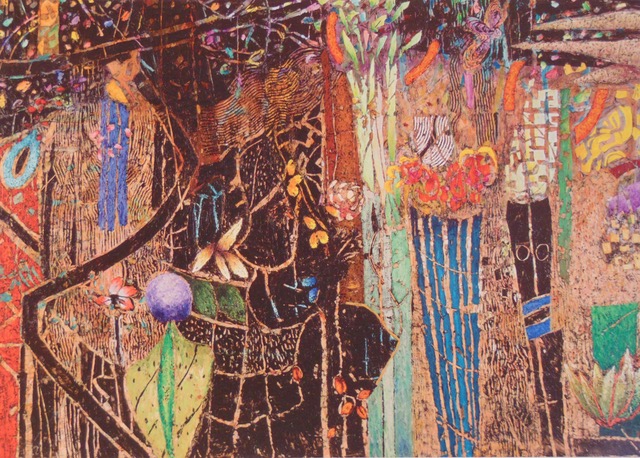

(Fig.4) Night’s Edge: 2011 84” x 100”: Thematically, I imagine this painting reflects the long evolution of the columnar form, originating as tree-trunks as a support for shelter, and later a formalized roof support in the columns of the Egyptian Tombs, and later the Parthenon. The richly colored columns gently leaning on each other feel like all of us beings, each in our costume, at home together and sheltered by our growth around us.

(Fig.5) Broadcast: 2010 42”x54” Not long ago I came upon a bush that was being visited by a dozen multi-colored large butterflies. Aside from the gift of that moment, I was, like Gulliver, miniaturized into the aerial space of the many small winged creatures that are also residents of our desert. The butterflies (and grasshoppers) in their colorful glory can make the many quieter shapes and colors of our desert more visible by their presence. In this painting Waid makes visible the life of short-flights, hoppings, scurryings, the markings of so many barely visible friends and the small-scaled gardens they see.

(Fig.6) Aravaipa: 2015 48”x72”: Is this a landscape? To my eye it is, but without the conventions of horizon line, earth/sky, or space. In a simple suggestion of a forest ground, life and death interact in the form of leaves, some growing, some falling, all carrying histories of their origins, implied but unseen, reminding me of how the smallest moments of the natural world are sufficient and complete, letting my own heart take comfort in whatever little garden I am now.

(Fig.7) Paleo: 2015 70”x60”: I had a painter friend who put a camera on post 4 feet off the ground, in the forest behind his Pennsylvania home. He programmed it to take a photo of the ground each day at the same time, for a year. Somehow it connected with my own experience of looking down on our earth from 30,000 feet, where there is a miniature map of my world that for a second I can see without belonging to it.

This painting (Paleo) is so rich in activity. But as my friend said about what he learned from 365 photos was ‘there are no seasons’. That is, our ideas about life are different from what is ‘just there’. Liberating what’s there from our thoughts about it releases a primal connection we have with what we call ‘beauty’.

While Jim Waid’s work reflects the long lineage of painting, his paintings also, like those in every generation of artists, contain new insights relevant to his own time. For example, ‘moving pictures’ (‘movies’) clearly influenced the rise of cubism at the beginning of the twentieth century, just as atomic theory influenced the pointillistic impressionism in the nineteenth. As I contemplate Waid’s work, I am reminded of the role modern chemistry has played in producing an explosion of color—brighter than in the past, some even psychedelic. Just in time too, because optical advances in micro and macro-photography open for painters like Waid a vastly expanded visual universe that is redefining how we see what is before our eyes, literally blowing our conventional representations of nature out of the water.

While these new tools are open to all of us, in Waid’s case, we can see them embedded in his years of observation of the Sonoran Desert. Joined to his kinesthetic mastery of the medium of painting, he invents absolutely new visual forms that physically capture as well as expand for all of us the presence of nature in our lives.

- Waid’s new book (Jim Waid: Paintings 2016) is available on his website, www.jimwaidart.com. His large public mural can be seen in the Tucson Federal Building at Broadway east of I-10 during public hours.

Andy Rush