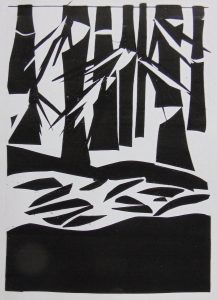

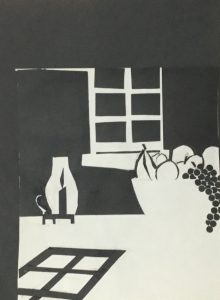

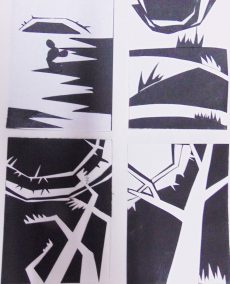

The Images that accompany this essay are student work, randomly selected from my recent cut-paper class assignments at The Drawing Studio.

In our Drawing Fundamentals classes, we break down the elements of drawing, for example, ‘line’ or ‘space’ or ‘light and dark’, into separate lessons to clarify the role of each. The study of what we call shape takes very special attention, because shape-scanning activates a very different part of the brain than other elements. It’s a skill that we share with all our fellow vertebrates, not just the higher-order mammals. All of us, not just art-learners, acquire a huge ‘shape’ vocabulary from earliest infancy. The ability to visually identify flat shapes is crucial for our survival as an organism.

In our Drawing Fundamentals classes, we break down the elements of drawing, for example, ‘line’ or ‘space’ or ‘light and dark’, into separate lessons to clarify the role of each. The study of what we call shape takes very special attention, because shape-scanning activates a very different part of the brain than other elements. It’s a skill that we share with all our fellow vertebrates, not just the higher-order mammals. All of us, not just art-learners, acquire a huge ‘shape’ vocabulary from earliest infancy. The ability to visually identify flat shapes is crucial for our survival as an organism.

Any study of the eye and brain quickly reveals that the whole act called seeing is very complex. Different areas of the brain become activated when stimulated by various aspects of optical phenomena. The eye miraculously assembles these activation patterns into one image. For example, color and tactility activate the limbic area of the brain, while the neocortex activates a matching process with already known images to turn shape into meaning. And while the ability to tell a story with images, or to express emotions through color or light are all learnable art skills, shape tends to be overlooked because shape perception and interpretation is a rapid-fire, largely unconscious process that started at birth.

Any study of the eye and brain quickly reveals that the whole act called seeing is very complex. Different areas of the brain become activated when stimulated by various aspects of optical phenomena. The eye miraculously assembles these activation patterns into one image. For example, color and tactility activate the limbic area of the brain, while the neocortex activates a matching process with already known images to turn shape into meaning. And while the ability to tell a story with images, or to express emotions through color or light are all learnable art skills, shape tends to be overlooked because shape perception and interpretation is a rapid-fire, largely unconscious process that started at birth.

When I was in the Marine Corps serving on naval ships, we ‘stood watch’ on the quarterdeck for four hours at a time, looking out to the horizon for any sign of other ships or airplanes. We were trained for this task by memorizing hundreds of black and white cards showing the silhouettes of domestic or enemy cruisers, destroyers, fighter planes or bombers, until we could recognize them within a tenth of a second.

When I was in the Marine Corps serving on naval ships, we ‘stood watch’ on the quarterdeck for four hours at a time, looking out to the horizon for any sign of other ships or airplanes. We were trained for this task by memorizing hundreds of black and white cards showing the silhouettes of domestic or enemy cruisers, destroyers, fighter planes or bombers, until we could recognize them within a tenth of a second.

From that first conscious ‘shape-training’, I also realized that ‘shape scanning’ goes on whenever our eyes are open, sorting out whether we are safe or not. Examples: a) soft and touchable vs. prickly or sharp; b) man-made (geometry) vs. wild (nature-made); c) already known vs. unknown, etc.

Once we are aware that shape (and the harmonic mixture of shapes, called ‘pattern’) is already a very highly developed visual vocabulary in our brain, we have a new and very useful insight for our own art. As with our other natural human skills (speaking, singing, movement), shape and pattern perception have evolved into an aesthetic practice. Just as speaking becomes theatre or poetry, body movement becomes ballet or drumming, or singing becomes opera, shape-scanning becomes art.

Once we are aware that shape (and the harmonic mixture of shapes, called ‘pattern’) is already a very highly developed visual vocabulary in our brain, we have a new and very useful insight for our own art. As with our other natural human skills (speaking, singing, movement), shape and pattern perception have evolved into an aesthetic practice. Just as speaking becomes theatre or poetry, body movement becomes ballet or drumming, or singing becomes opera, shape-scanning becomes art.

What began as a survival mechanism eventually provides all of us with a deep aesthetic satisfaction that we actively pursue. In our homes, we surround ourselves with tapestries, wallpaper, bedspreads and rugs, flowers – the decorative objects of our domestic life— extending even to the clothes we wear and the meals we serve. We take such pleasure in pattern because we have long been engaged with pattern at a deeply visceral level.

What began as a survival mechanism eventually provides all of us with a deep aesthetic satisfaction that we actively pursue. In our homes, we surround ourselves with tapestries, wallpaper, bedspreads and rugs, flowers – the decorative objects of our domestic life— extending even to the clothes we wear and the meals we serve. We take such pleasure in pattern because we have long been engaged with pattern at a deeply visceral level.

Whatever anyone who makes art thinks he/she is communicating, it’s important to know that the shapes we use to make art are speaking into an already sophisticated vocabulary in everyone’s brain. If an artist is unaware of this, he/she has almost no chance of connecting more than superficially with viewers, because the aesthetic stability that shape/pattern provides to the art message may not be cooperating in a way that supports the intention of the artist.

To better awaken our understanding of pattern-making and the role of shape as the bedrock of visual communication, I have created a Drawing Fundamentals 3 class at The Drawing Studio called “Cut Paper” in which we use only a sketchbook, black paper, scissors and a gluestick. This technical simplicity helps block any wandering into the swamp of illusion and concept, so that we can focus on the role of shape alone.

To better awaken our understanding of pattern-making and the role of shape as the bedrock of visual communication, I have created a Drawing Fundamentals 3 class at The Drawing Studio called “Cut Paper” in which we use only a sketchbook, black paper, scissors and a gluestick. This technical simplicity helps block any wandering into the swamp of illusion and concept, so that we can focus on the role of shape alone.

Class assignments (note the examples shown with this essay) involve creating images by cutting black shapes and combining them on white paper or white shapes on black paper. Working this way makes the point that, while our writing culture mostly puts black on white, the artist can work either way, or both together, an insight that can be very freeing to one’s visual imagination.

And what is learned in the process?

1. Every shape, whether foreground or background, communicates into our own shape vocabulary. In addition, shape and pattern give us the abstract platform that supports the rest of our art ideas, such as narrative, or spatial meanings, or texture and color—because like it or not, shape and pattern are what the eye unconsciously registers before other areas of the brain respond emotionally or interpretively.

1. Every shape, whether foreground or background, communicates into our own shape vocabulary. In addition, shape and pattern give us the abstract platform that supports the rest of our art ideas, such as narrative, or spatial meanings, or texture and color—because like it or not, shape and pattern are what the eye unconsciously registers before other areas of the brain respond emotionally or interpretively.

2. Shapes have emotional, dramatic and descriptive power mostly at a subliminal level of vision, precisely because they are so directly connected to our survival. In addition, every person’s shape vocabulary is simultaneously culturally determined and personally unique. By becoming conscious of the shape-patterns we all share, or in some cases do not, we have a new window that lets our own art connect and resonate more deeply with others.

2. Shapes have emotional, dramatic and descriptive power mostly at a subliminal level of vision, precisely because they are so directly connected to our survival. In addition, every person’s shape vocabulary is simultaneously culturally determined and personally unique. By becoming conscious of the shape-patterns we all share, or in some cases do not, we have a new window that lets our own art connect and resonate more deeply with others.

3. Whatever ideas we are trying to convey about a subject, like spatial perspective, color and light, texture, or narrative, the eye also draws a deeper satisfaction in the ancient patterns underlying the other aspects of the art. In fact, even when we are ignorant or have no interest in the narratives of long past or foreign art, the shape/color/pattern still can keep us connected aesthetically.

3. Whatever ideas we are trying to convey about a subject, like spatial perspective, color and light, texture, or narrative, the eye also draws a deeper satisfaction in the ancient patterns underlying the other aspects of the art. In fact, even when we are ignorant or have no interest in the narratives of long past or foreign art, the shape/color/pattern still can keep us connected aesthetically.

4. The fact that patterns are often optically ambiguous is part of the pleasure of looking at them. Seeing in more than one way at the same time can produce a kinesthetic energy that gives us richer interpretations. It is a moment we sometimes call ‘delight’ (spiritual illumination) that is the core experience of looking at art.

This essay about art learning is of course not ‘it’. My words are like the color photo of a juicy hamburger on the cover of the café menu that may produce saliva, but should not be mistaken for food. I invite you to enroll in my cut-paper course (to be offered in October 2017 and March 2018) for a useful introduction to the practice of conscious ‘shape-scanning’ as a life skill as well as an art skill.

This essay about art learning is of course not ‘it’. My words are like the color photo of a juicy hamburger on the cover of the café menu that may produce saliva, but should not be mistaken for food. I invite you to enroll in my cut-paper course (to be offered in October 2017 and March 2018) for a useful introduction to the practice of conscious ‘shape-scanning’ as a life skill as well as an art skill.

Andrew Rush

2 Responses to The Role of Shape/Pattern in Art (and in Life)