On a hot summer day in St. Louis when I was a boy of twelve, our pick-up baseball game in Forest Park was rained out in the third inning. Seeking quick shelter until my mom could come later at the appointed time to pick me up, I ducked into the nearest public space, which turned out to be the St. Louis Museum of Art.

Looking back, I realize that my mild young interest in drawing turned into a life career on that day. That first visit to a museum introduced me to a world I had been looking for, my artist family. Ever since, museums have been my second home. In the quiet solitude of the museum I studied the handiwork of my new relatives, first in deep admiration, then eventually and more practically came to understand how art was made.

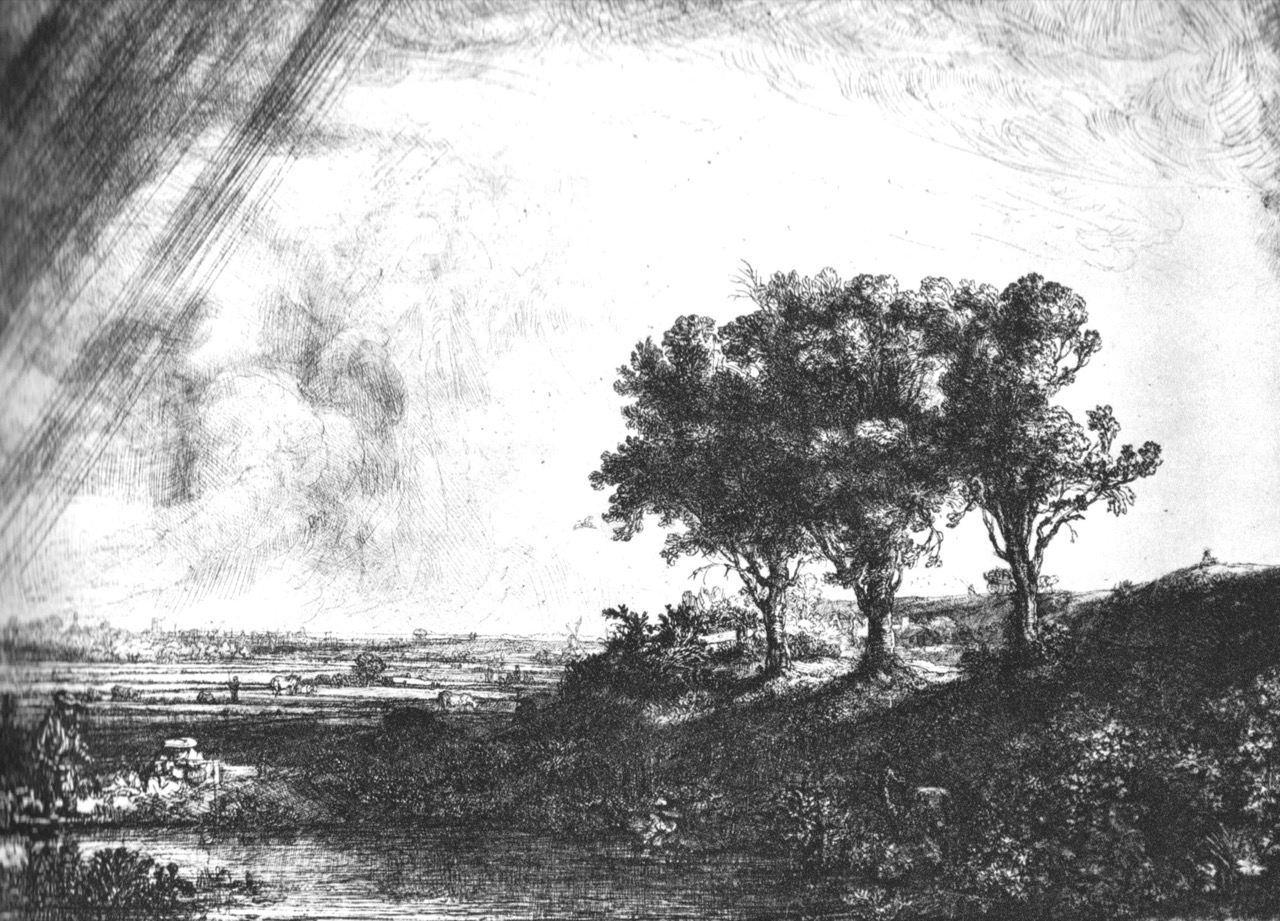

Years later when I was first learning to make prints using the etching medium, I became aware of Rembrandt’s prints on copper, and was fascinated by how he could evoke light using only the crossing-hatching of lines made with the etching needle. I had only seen reproductions in books until I was in the Rijksmuseum in Holland in 1959 (thanks to a Fulbright Artist Grant), where I spent days with his original etchings including the Three Trees, shown with this essay.

Three Trees by Rembrandt van Rijn,1643. 8 3/8” x 11 1/6″, etching on copper

This landscape is perhaps one of a half dozen of Rembrandt’s most well known copperplate etchings. It has been reproduced in books and catalogues thousands of times, not only because it is one of a few pure landscape studies he did in his lifetime, but also because it conveys a broad spiritual dignity that makes it one of his most memorable works in any medium. Even for people who don’t have any experience of etching, Three Trees still holds a unique emotional power, hundreds of years later.

On that day in Holland when I first saw it in the original, I had by then my own practice of etching that let me look more deeply, more technically, and without the hazy filter of reproduction. I could then see not only how Rembrandt drew the lines through the hard-ground to expose the copper, but how he also controlled the strength and the timing of the biting acid to set the depth of each group of lines in a way that created an illusion of space between one layer of lines and another. This ‘time-biting’ also let him control the cleanliness of the biting so that there lived in the darkest zones of the cross-hatched etched lines little islands of light (the untouched copper), invisible in any reproduction but clear in the original.

Because his precision of each layer of line biting was so clean, his darks become crisply alive and spatial. They are not flat like a woodcut, but intricate, mysterious and filled with light.

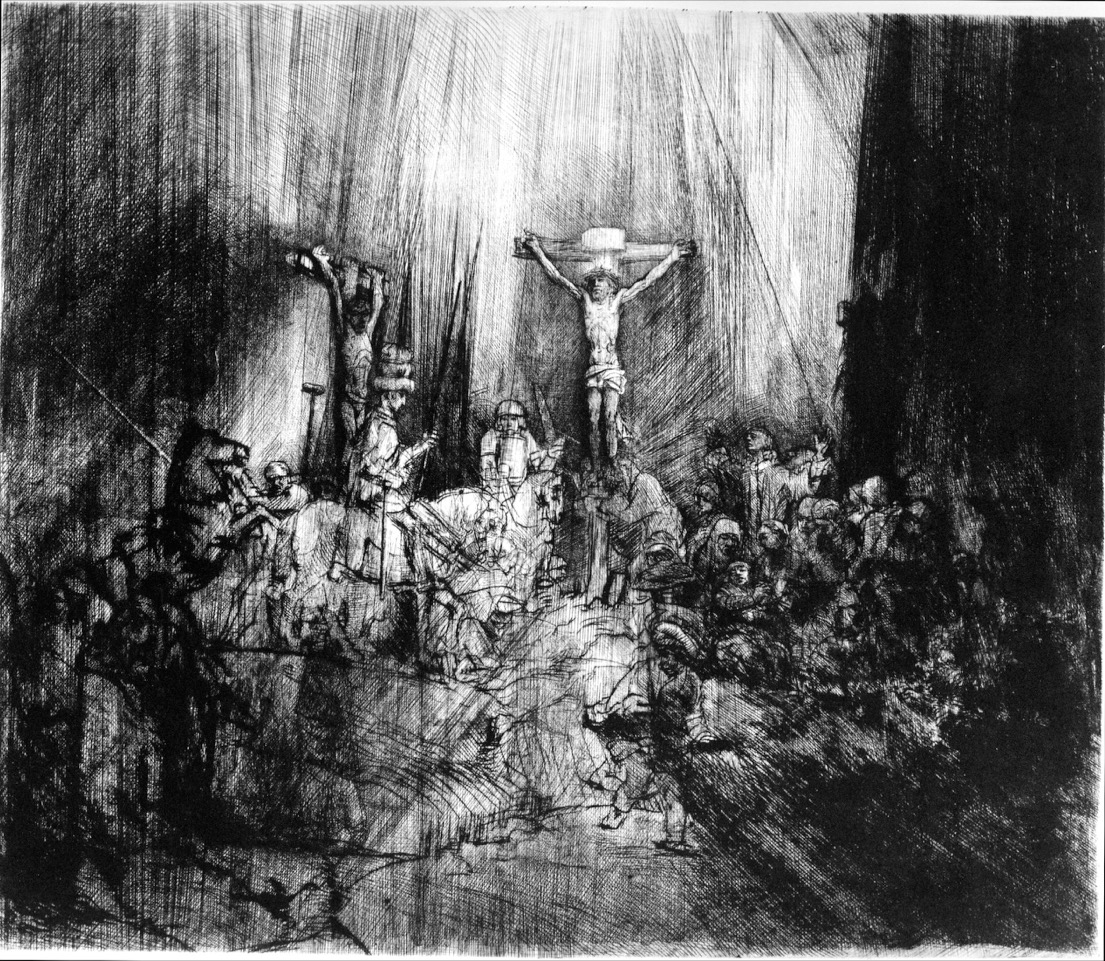

I also include Rembrandt’s Crucifixion etching with this essay, of which there exist five stages showing his many changes to the plate in order to achieve the brilliant illumination of light he achieved so simply with such simple black and white line work. I recommend studying this etching to see the wide range of light effects he achieved with layer upon layer of lines crossing over each other.

The Three Crosses by Rembrandt van Rijn, 1653. 15” x 18”, etching on copper, 5th state.

Because of our museums, we artists have direct access to the work of our long past colleagues. In this sense, I can say that this precision of Rembrandt’s exact technical skills with metal and acid is a direct gift from him to my own printmaking. I have always remained grateful for the essential opportunity that our public Museums (which were free when I was a boy, by the way) offer for us all to learn from original works of art –on the physical level, on the aesthetic level or the spiritual level– what no reproduction can show completely.

As a coda to this discussion about the Three Trees, I have written often about the importance of connecting one’s personal art practice to the most intimate aspects of one’s life, because I believe intimacy is the source connection that animates great art and artists. So I think it relevant to note that the year before Rembrandt made the Three Trees, his wife Saskia, the one woman in his life with whom he was most deeply in love, died unexpectedly. The silent dignity of this print, created shortly after Saskia’s death, suggests to me how Rembrandt may have retreated to the quiet consolation of the natural world in order to manage his grief.

I notice that I too am in my studio almost daily, creating intimate landscapes of my desert, an enormous consolation after the death of my beloved wife of 50 years, Ann Woodin just over four months ago.

Andrew Rush