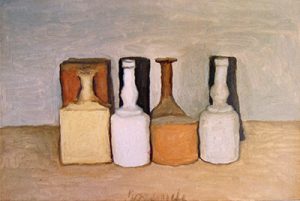

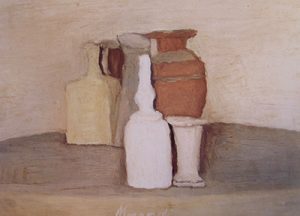

As a young artist studying in Florence, Italy in 1958, I happened one day into a gallery that was showing some small modest paintings of bottles and other little table objects by an artist from Bologna. As I contemplated each work, something seemed clearer in my personal search for my own art path. Not long after, I found a newspaper photo of the artist that I pinned to my studio wall, where it lived for years as a kind of private talisman that reoriented me whenever I lost heart or direction.

More than fifty years later, I happened to read about the first American retrospective exhibition of that artist, Giorgio Morandi (1889-1964) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Without another thought, I cleared a long weekend in my busy life and flew to New York, where I spent hours contemplating the journey of Morandi’s life’s work, full of appreciation for the clarity he slowly earned for himself. As I flew back to Arizona, I realized for the first time that while I’d long known of Morandi’s influence on my own art life, I hadn’t realized how his work had contributed to bringing The Drawing Studio into being.

More than fifty years later, I happened to read about the first American retrospective exhibition of that artist, Giorgio Morandi (1889-1964) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Without another thought, I cleared a long weekend in my busy life and flew to New York, where I spent hours contemplating the journey of Morandi’s life’s work, full of appreciation for the clarity he slowly earned for himself. As I flew back to Arizona, I realized for the first time that while I’d long known of Morandi’s influence on my own art life, I hadn’t realized how his work had contributed to bringing The Drawing Studio into being.

What exactly did Morandi’s images contribute to TDS? Simply put, he showed me that the quiet practice of looking into the humblest corners of one’s daily life was totally sufficient as a pathway to manifest one’s inner vision. In a way, my entire certainty about the central importance of the skills of observation began on that day in Italy when I first saw Morandi’s small, intelligent, and elegant paintings and etchings.

What exactly did Morandi’s images contribute to TDS? Simply put, he showed me that the quiet practice of looking into the humblest corners of one’s daily life was totally sufficient as a pathway to manifest one’s inner vision. In a way, my entire certainty about the central importance of the skills of observation began on that day in Italy when I first saw Morandi’s small, intelligent, and elegant paintings and etchings.

From his inspiration began my journey that brought The Drawing Studio into being forty years later. Because it became clear to me that I was living in an era of relentless transformation of mass visual media that revealed the limits of the specialized art schools of my youth. That indeed a new kind of curriculum in the rigorous practical education in how we see is clearly necessary for every one of us who intends to participate in the conversations of this century, whether we are artists or not. A general visual education is now as practical to modern life as reading and writing.

Hence, the Fundamentals of Drawing Program* at TDS a skill-based education that goes far beyond the conventional stereotype of drawing as something one does with a pencil. Its deceptively simple first assignments address how we can only see what we are prepared to see. These first exercises often rattle one’s comfort zone, but also quickly expose the much richer adventure that lies waiting.

Hence, the Fundamentals of Drawing Program* at TDS a skill-based education that goes far beyond the conventional stereotype of drawing as something one does with a pencil. Its deceptively simple first assignments address how we can only see what we are prepared to see. These first exercises often rattle one’s comfort zone, but also quickly expose the much richer adventure that lies waiting.

For example, we discover that the marks we make to record what we see do not work like a camera, because drawing carries our very physical DNA into the process. Even from the time we were happily scribbling as a child, the feeling of doing it is primitive and deep, in an inside-nourishing way. We are not just looking when we draw, we are in a sense creating what we are looking at. This can be an unsettling sensation at first because it challenges the notion of drawing as representation as opposed to a process of personal engagement with our subject that is much more intimate, involving our feelings and our inner eye, as Morandi shows us..

For example, we discover that the marks we make to record what we see do not work like a camera, because drawing carries our very physical DNA into the process. Even from the time we were happily scribbling as a child, the feeling of doing it is primitive and deep, in an inside-nourishing way. We are not just looking when we draw, we are in a sense creating what we are looking at. This can be an unsettling sensation at first because it challenges the notion of drawing as representation as opposed to a process of personal engagement with our subject that is much more intimate, involving our feelings and our inner eye, as Morandi shows us..

As with learning anything new like drawing, it is natural to start with small steps, using simple objects, often painted white to help isolate their form and shape. Later, as students acquire wider familiarity with tool and measurement skills, we expand into working in different ways, inspired by a variety of different kinds of “things”, both natural and man-made. Along the way we are also broadening our vocabulary of mark-making and experimenting with different tools with which to look.

As with learning anything new like drawing, it is natural to start with small steps, using simple objects, often painted white to help isolate their form and shape. Later, as students acquire wider familiarity with tool and measurement skills, we expand into working in different ways, inspired by a variety of different kinds of “things”, both natural and man-made. Along the way we are also broadening our vocabulary of mark-making and experimenting with different tools with which to look.

Then one day, the ante goes up. Instead of more “things” to draw, students arrive at a session where a small square mirror is propped up at each work station. The assignment: to make a self-portrait working for accuracy in two hours. After an initial stunned silence, there often comes a kind of helpless panic in the form of joking (“You’re not serious, are you?”) or tears (“God, those wrinkles!”). But with some encouragement, the student quiets down to confront the task to see if she can indeed address the reality of that face in the mirror with the same skills with which she’s been exploring small objects.

Still, something is different. When we draw from our own face, we recognize we are stepping over a threshold into a new level of how seeing works, because for the first time we are presenting ourselves to ourselves as subject. Even through the filter of a self-conscious ego, we are able to make a courageous attempt to penetrate a new level of perception. The conversation we now can call “art” starts here, where the inner eye and outer eye begin to meet each other..

Still, something is different. When we draw from our own face, we recognize we are stepping over a threshold into a new level of how seeing works, because for the first time we are presenting ourselves to ourselves as subject. Even through the filter of a self-conscious ego, we are able to make a courageous attempt to penetrate a new level of perception. The conversation we now can call “art” starts here, where the inner eye and outer eye begin to meet each other..

It is here that the great artists like Giorgio Morandi have been waiting for us.

*Note 1: An introductory flier about the TDS Drawing Fundamentals Program is available upon request.

Note 2: An earlier version of this essay first appeared in The Nature of Drawing, TDS 2010.