I am always intrigued by those artists of the past who, through drawing from observation, invented a unique place for themselves in their own time. For example, I have written about Beatrix Potter, who actually created the category of books for children with her small animal drawings that led to Peter Rabbit.

Any printmaker who has ever explored the art of wood engraving knows of Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). Like Potter, Bewick was not widely known in museum circles. Yet in his day he was one of England’s most respected artists, a publisher and life-observer known only by his many small wood engravings (3” x 4”ca) that accompanied books of his own creation.

Should you become intrigued by his work from this essay, I recommend Nature’s Engraver: The Life of Thomas Bewick by Jenny Uglow (2009, Univ. of Chicago Press. Here is that author summarizing his skills:

Should you become intrigued by his work from this essay, I recommend Nature’s Engraver: The Life of Thomas Bewick by Jenny Uglow (2009, Univ. of Chicago Press. Here is that author summarizing his skills:

“Bewick appears to have had a faultless sense of exactly what line was needed, and above all where to stop, as if there were no pause for analysis or reflection between the image in the mind and the hand on the wood. This skill, which has made later generations of engravers pause in awe, could be explained as an innate talent, the je-ne-sais-quoi of “genius”. But it also came from the constant habit of drawing as a child, (joined to) the painstaking learning of technique as an apprentice …””

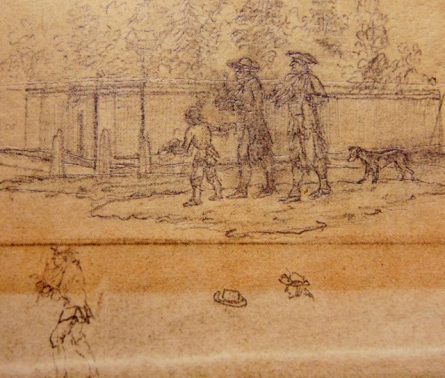

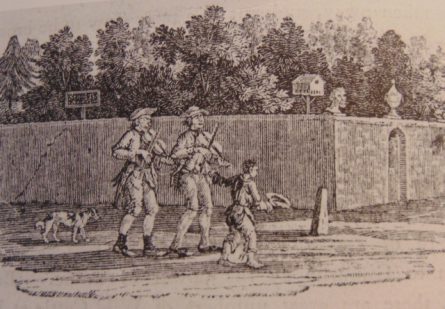

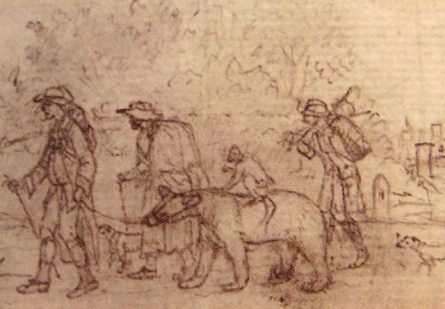

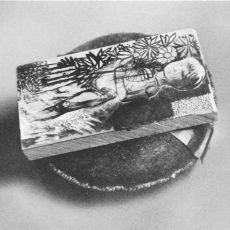

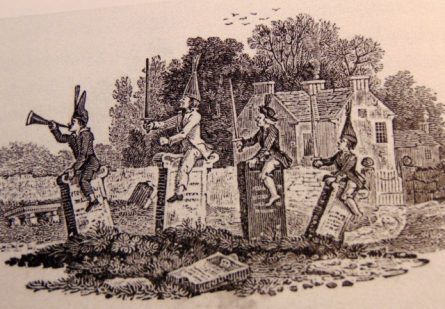

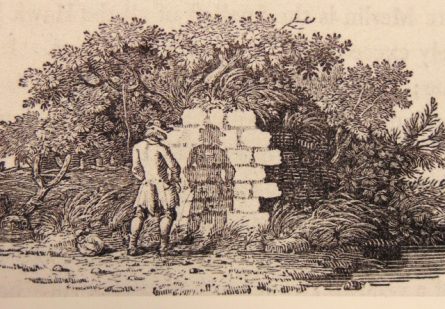

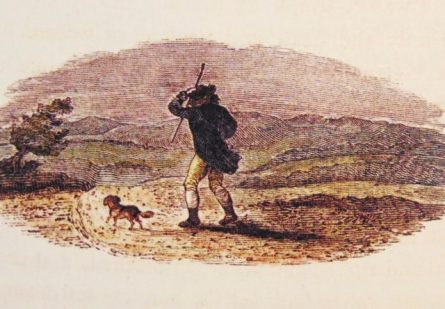

I was already forty y ears old when Bewick’s tiny wood engravings inspired me to learn the technique. Working on an end-grain woodblock in which the image is incised, line by line or dot-by-dot with an engraving tool, I discovered the level of skill it took to produce his profound windows into daily life as little (2 x 4”) tailpieces (as he called them) to finish out a blank space at the end of a printed book text.

ears old when Bewick’s tiny wood engravings inspired me to learn the technique. Working on an end-grain woodblock in which the image is incised, line by line or dot-by-dot with an engraving tool, I discovered the level of skill it took to produce his profound windows into daily life as little (2 x 4”) tailpieces (as he called them) to finish out a blank space at the end of a printed book text.

It is also clear that Bewick drew from the close study of life. After trying his hand at big city illustrator jobs, he opted for a quieter life, returning to his regional origins, where his eventual partnership in a small book-making business gave him the opportunity to illustrate his own projects.

As his own book-printer, he realized that wood engraving not only outlasted metal, but could be locked into the metal typography chases of the printed books of the time, allowing him to use his own brilliantly original engraved illustrations to accompany books sold on the popular market. (Up until that time, illustrations were printed separately from text, then ‘tipped in’ the the book by hand.

Bewick produced from his own publishing company many illustrated books, including a complete history of British Birds in (1797) and later a second volume on waterbirds (1804).

Bewick produced from his own publishing company many illustrated books, including a complete history of British Birds in (1797) and later a second volume on waterbirds (1804).

An aside: when he was 77 he was visited by the American James Audubon who was then a young man seeking someone to publish his now famous watercolor studies of American birds. Bewick inspired and helped him to find the very original lithographic procedures of modern printmaking then emerging.

Simultaneously, his so-called ‘tailpieces’ mentioned earlier earned him a devoted following as he depicted countless human moments, humorous, thoughtful and at times charming to ordinary people. It is in these little engravings that one can find the very fresh essence we call a work of art, as noted earlier by his biographer, ‘the jej-ne-sais quoi of genius’, that one-ness of mind and hand that invents as he works.

It is the same essence that we find in Goya’s great Disasters of War etchings, or Daumier’s daily political lithographs in the Paris press, or in the Piranesi Italian etchings of ‘I Carceri’ (prisons).

One might ask, given the modest size of his work, why was Bewick so beloved in his time? I believe he found a compelling way to add original visual art to mass communication. In this sense, he was an early harbinger of modern computer graphics, in which image-based communication is available to more and more people.

Bewick’s work is also, in my view, relevant to our philosophy at The Drawing Studio, where we encourage people from all walks of life to master the hand skills and tools of art-making. Why? Because the physical practices of art-making carry, like Bewick’s skills, a kinesthetic directness that most empowers the words. The ‘message’ is now complete. One person can communicate as the brain was designed, from its marvelous two hemispheres of reality. Now the highly visual channels of the right brain (that reveal the creative/musical/spatial and physical energy part of life) can for the first time join the highly developed linear skills of intellectual thought in the work of one person.

Most new media arrive on the scene quietly. The iPhone is not only or even a phone. The ‘car’ (from carriage) is no long pulled by horses. The marriage of words and images in the personal computer is like Bewick’s publishing shop, now in the hands of anyone willing to learn anew.

Copyright Andrew Rush 2016